Ruby Ray and Punk Surrealism:

The SF Punk Rock Ground Floor photo documentarian and her splendid evolution

Ruby Ray: The Reflecting Skin

Ruby Ray is a punk photographer. Self taught and DIY she has chronicled and interpreted 40 years of punk and post punk, created multi-media performance and traveled the world. Everyone from Devo to the Germs found their way into her lens. Long before there was Facebook or Twitter or an Internet, Ruby’s work was appearing in underground tabloids and zines documenting an undiscovered landscape. Her captures were instantaneous. Her aesthetic apocalyptic. Her vision went beyond the apocalypse, to where strange new forms come into being and dreams take shape and walk in the photographs and collages that she continues to work on. Ruby has something to say. I met with her in her charming North Beach apartment at the end of 2015. Interview Joe Donohoe

S: Punk was sort of apocalyptic in its images. The hippies wanted to get back to the garden but the punks were partying in the End Times.

RR: Well my first zine was called “Worldwide Flipout.” I collected pictures from news articles and the zine was about the apocalypse I felt was imminent. I made about fifty copies that were promptly stolen. “I must be prepared for ‘Worldwide Flipout’” has always been in the background of my life. I’ve always had an apocalyptic frame of mind.

S: You did a photo shoot in a tire junkyard with Exene Cervenka where you said: “This is our environment.” You saw that a lot in punk instead of images of nature and stuff that was “beautiful.” Bleak looking buildings or tower blocks. On the first iconic Ramones album, the cover photo shows them all standing in front of a brick wall. The mainstream at the time, when not about happy coke fueled disco dancing, was all about John Denver, California Country rock and redwood trees, but here’s this Blackboard Jungle like picture from Hell’s Kitchen in New York.

RR: I liked to take photos of bands with backgrounds of urban decay — apocalyptic scenes. I always wanted to put something extra in the photo that said something apart from the overt content. I wanted a good photo of the band or the people, but I’d want an allusion to something else at the same time. This photo has a dump background and it was a super fun place to shoot.

S: Is that [industrial San Francisco neighborhood] China Basin?

RR: Yeah but the dump is no longer there. We had a blast because there was so much stuff we could find! When I started working with Factrix I got hip to factory architecture. There was a lot of that in punk and post punk. Throbbing Gristle/Psychic TV were really into images of industrial landscapes. One of the photo collages I’ve just made is very apocalyptic. It’s called “In the Tower.” I took the photo from the top of the World Trade Center in New York prior to 9/11 obviously. I had the slide from punk days and I scanned it.

S: Urban decay was a kind of subversive aesthetic in the ‘70’s in and out of punk. You see it in Hip Hop too.

RR: I think punk was political too though. Not in the sense of “I’m a communist” or “I’m a radical leftist” or “anarchist.” It was more a sense of: “Wow this is what politics really is — a bunch of bullshit.” All the politicians were liars and the CIA was/is engineering wars — just finding out about all that stuff — we saw it as bullshit and wanted to ridicule it. This was different from the Sixties thing of “Get involved. We’re all in it together.” Maybe it’s anti-political.

S: Well if you look at the differences between the hippies and the punks, the hippies were “peace, pot and microdot,” organic farming, folk music. The punks were just snarky about all of that. The hippies, a lot of them, ended up just wanting to be “mellow” and not wanting to rock the boat. It seems like every time a Democrat becomes president, after a long Republican Administration, everybody wants to take it easy and that’s really dangerous. Punk seemed really subversive with its general lack of overt political statements, at least initially. Vale also called it the “last naïve culture.”

RR: It seems naïve now from my level of education and perspective, but at the time I feel we were onto an aspect of how the media was conditioning a lot of people’s reality. We weren’t taking television at face value and, I believe, were onto something that was more true. We saw through the brainwashing that was going on around then. Brainwashing that has continued until now. People are completely brainwashed I think.

S: Give me some examples of that from the mid-Seventies.

RR: Well the whole idea of using television commercials to control people — that was one thing we saw. They were using this thing called embeds: laying a word or image over another image and just letting it be seen for a split second, but it would register in your consciousness and effect you. Advertising was doing that quite regularly. It became illegal but I think they still do it.

S: Look how fast television and film are edited now.

RR: Yeah I can’t stand the “flashing” quality of today’s TV, video and films. TV news is especially like that. The first ten seconds is the flashing logo of the news show with a graphic of the world spinning around and flashing and then words at the bottom of the screen scrolling along faster than a lot of people can read them. This is all before you even get to the actual news. It stimulates the brain but doesn’t give you any actual information. It’s like a slide show. I haven’t had a TV for ten years now but the Internet is becoming like TV It’s gotten to that, and they’re not going to let up. The thing about the Seventies is that the anti-materialism of the Sixties turned into this very materialistic era. The imagery associated with needing to have all kinds of stuff really got pushed. We punks, well the people I knew, wanted to get away from all of that. We didn’t want to work 40 hours a week to buy stuff, and not be doing anything else. We wanted to go out to punk rock shows and meet people and talk about artists we liked, and books or whatever. The mainstream didn’t like that and tried to put punk down because it wasn’t a materialistic movement. It did become a materialistic thing later on, but that’s because the zines, records, posters, clothes that got made were so rare. There wasn’t much of it. The people with money wouldn’t put anything out. There were few big record companies that would’nt touch punk rock. Warner Brothers pressed the Ramones but that was a notable exception. The Ramones, and a few other bands, got major label releases. In San Francisco our scene was very different.

S: What was unique about the San Francisco scene?

RR: Well largely we didn’t get any recognition, so we just tried to stay true to whatever we were building within the group of people that we were part of. It wasn’t like we planned anything. We were always interacting with each other though. There wasn’t the ego thing as much. It was a very supportive scene. The fans were just as important as the bands. We were all interactive. “Now it’s your turn to go up there! What are you going to say? Tell us something that will really move us. Give us something real.” It was about pushing people to be crazy but it was super fun. It was only later, when the mosh pit thing really got too violent, that the punk scene altered in a way different from what I was familiar with. But I was in New York by then.

S: There’s a lot of publishing about punk now. It’s like anyone who went to CBGB’s wrote a memoir. You’ve mentioned did have a hard time finding a publisher for your book, indicating to me that there’s probably a glut of books on punk rock. But that probably means there’s an abiding interest in the subject. Definitely the London and New York scenes, to a lesser extent Los Angeles, the Midwest and the American Northwest.

RR: San Francisco has a kind of cult appeal because it’s less known and less of it came out on record. I think that younger people who are interested in punk rock search out the details. But I think we had incredible bands. Some of the best. I went to London in 1978 and by that time things were starting to die down. I thought “Oh shit I should have stayed in San Francisco because it’s really happening there and I’m going to miss a lot of shows.” I realized what an amazing scene we had when I got to contrast it to England. It was really different over there. Do you know Michael Reed? He’s one of the Punk Rock Sewing Circle. English, tall. He grew up outside of London and saw the whole scene develop. He knew Sid Vicious when Sid was into David Bowie and had long hair. Punk came out of nowhere and was probably really fun when it first happened. In England punk became hugely popular and the Sex Pistols were huge —London was different from San Francisco by the time I showed up.

S: You mentioned the Punk Rock Renaissance that you helped to put together with the Punk Rock Sewing Circle, that also put on the Punk Rock Home Coming the year before that. Could you talk about that?

RR: Yes. It was a really successful series of events. We had Cheetah Chrome this year and James Williamson from the Stooges came out and played two songs with Cheetah Chrome’s band. We also had Alice Bag and the Mutants, all playing here in San Francisco. That was really cool and really exciting. It took a lot of work. Then we did two photo shows in 2015 —this past year. The live music events were in 2012 and 2013 and then this year, but I don’t think we’re going to do anymore.

S: People are getting up there. Rockers with walkers. So you were coming out of working in Tower Records in the ‘70’s, which was a pretty big chain store that had a lot of pre-Internet alternate media. Independent magazines, small press books, movies…

RR: Yeah Tower was great. It’s gone now. I worked in their store in New York City and worked in their International Music Department, believe it or not. I was really into Middle Eastern music and we had a lot of Middle Eastern recordings in our stock. It was a huge store. Thanks to them Search and Destroy, who I worked with, were able to keep going because they were the one organization that actually paid.

S: When did you become aware of punk rock and what was appealing about it to you?

RR: Well I’d been working in record stores for quite a while going back to working at 2 record stores in my home town of Buffalo, New York. That’s how I really got into music, though I’d always been interested. I met Patti Smith in 1973, before she even started playing music. She came to Buffalo and she was part of a rock and roll writer’s convention at Buff State University. I got to shake her hand. A very limp shake I’ve got to say, but I was impressed by her and I liked her writing in Creem Magazine. She used to write these very beautiful articles that were very dream like. Patti was the start of it for me. I didn’t really hear about English punk rock because Tower didn’t get any of the English papers, but Vale worked at City Lights and they got NME and Sounds. I used to see Vale around and I wondered who he was. This was at a time I was looking for new inspiration. He came into Tower one day to try to sell copies of Search and Destroy #1 and I just had to introduce myself. Tower had a great set-up for taking consignments. Usually you had to be connected with a distributor to get into shops. Distributing magazines was one of the hardest issues to deal with at that time. Distributors were almost like the Mafia in that way. Search and Destroy was how I found out about punk shows in San Francisco. I was totally sold when I went to see the Dils. I thought “Wow, this is what’s going on.” I took that turn and never went back.

S: The memory of this is fading but there was a real cultural shock when punk first appeared. In the United States after Vietnam and Watergate, the World War II generation and the generation that had been kids in the Sixties, wanted everything to be “calm” and “mellow.”

RR: Yeah a very “Marin County” sort of vibe.

S: I love the look of disgust on your face when you say that.

RR: [laughs]

S: It seems like there was a censorship in music on anything that challenged anything. The social critique had been removed.

RR: Punk was totally censored in San Francisco. In other cities it was a little different. New York had a different kind of scene and LA is a music capital, so punk got written about there. Punk in San Francisco didn’t really get written about outside the pages of Search and Destroy. It did catch on with the people, because the people were looking for something real. After Mayor Moscone died, punk was really harassed. George Moscone acted like he wasn’t bothered by it. Under Diane Feinstein’s mayorship the police started parking outside of clubs and breaking stuff up and harassing people who were just hanging out. And it wasn’t like we were rampaging or rioting. We were having a good time. We were having these great shows and gathering and talking.

S: If you look at footage of the Sex Pistols on 1970’s British television they’ve got short hair, straight leg jeans. Everyone else is wearing polyester flared pants and puffed up hair. The Sex Pistols look sort of normal and the Normals don’t. Punk really didn’t look that weird.

RR: Now it doesn’t! But it looked really weird then. You knew who the people were who were punk if you saw them. Just black pants and a black jacket looked weird. Most people didn’t wear all black. Some kids came up to me on the bus one time and asked: “What are you?” Of course we did have wild hair. So that attracted a lot of attention. It wasn’t a daytime thing. It was better to be out at night because of the attention you attracted. It was considered a very dangerous look, but it’s a look that stayed.

S: Vale once said that punk, in some ways, was an aesthetic revolt as opposed to a political revolt.

RR: Well we thought we were going to start a revolution. That was the naïve part of punk. The hippies thought they were going to start a revolution back in the Sixties too. We saw where all of that went. As far as an apocalyptic sensibility went, a lot of people my age, when we were kids, the Cold War was going on. We were told the Russians could bomb the US at any time. We had air raid drills in school. They would play a siren and we had to go into the closet and turn off the lights and be quiet. That would scare the heck out of me. We had to practice getting underneath our desks in school. This was going on for a couple of years. I was raised Catholic and went to Catholic School for a while and I liked the nuns okay, but in church they would always finish by saying: “God save the world. God save Russia.” When you’re a kid you have a small perception of what the world is so you would think: “We’ve got to save Russia.” This kind of thing just got put into your mind at an early age. Something, I felt, was going to happen and nobody knew when. But maybe something good will happen.

S: Well the 1950’s Cold War fears seemed to disappear with the fall of the Berlin Wall in the 1980’s. Then you had ten years of Internet porn and relative peace until 9/11. Now we have to be afraid of terrorists setting off dirty bombs in New York.

RR: Well they probably will. I don’t know. I hope we stay safe. Some people think we’re safe but I don’t think we’re living in a safe period.

S: Is any period safe? It seems like life is dangerous.

RR: I think safety is only in the mind. Maybe I’ll stay in my house for a while. I can do art with my computer. I’ve always made due with what I have. I’ve never really had any money and I’m still not making any money. I have more “fame” than I ‘ve had in my past, but I still have trouble with my bills and eating. With my computer I can reach the world and get my art seen before a global audience. That’s the focus of my work now. You can pay $5 and see my e-book on line. Anyone in the world can access that if they want. I designed a book for my friend David West and put that on the same e-site called “Amusedom.com.” You should put your books on there. I just talk to my friends and try to make them realize there’s a lot of good to technology. You’re a Luddite?

S: No. I’m not a Luddite. I’m just not an unreflective technophile. I think the Internet has destroyed a lot of culture and the ability of people to make a living creating culture.

RR: It sure has.

S: Unless you’re involved in making Hollywood movies. I think journalism is being destroyed. I don’t think this is happening because the technology exists. I think it’s happening because of the kinds of paradigms that are embraced by Silicon Valley and that are shared by the tech elite globally: We need bigger, we need more money, more efficiency, more profit — monetarize everything. Nothing matters but profit. This extends to the fields of health and education and it’s poisoned everything, but things can change. How did you go from being into music and working in a record store to being into photography?

RR: When I look back I remember that I did have cameras in high school and I was always posing for snap shots with my friends. I continued to do that — setting up photo shots with my friends. Jokey photos. One of my boyfriends thought I should become a photographer so he asked a friend of his who was going to South America to leave him their camera and it was a good camera. My boyfriend gave it to me and I started taking photos with it. I was living on Chestnut Street in North Beach, near the Art Institute, and there was a community center there and they had a dark room. I took classes on how to develop film and got really into that. It was cheaper for me to develop my own film than have it developed because I didn’t have any money. Back in those days I would save 30 cents to go to Doggy Diner right around the corner for coffee. Doggy Dinner is gone now. I was really interested in the Symbolists and the Decadents as far as what kind of art I was looking into. I would apply themes I’d see in those movements and apply them to what I was photographing. I would go for dark shadows and weird angles. I liked stuff that was mysterious. I was also inspired by Surrealism. I would just walk around the city and take photos, develop them. I was in the North Beach Photo Faire that used to be held in Washington Square Park. Then I met Vale and worked with Search and Destroy and ReSearch. I’m not formally schooled in the arts.

S: You’re an autodidact?

RR: Yes. Definitely. I was looking for something new. At the time I was looking for the appropriate media. I wanted to work in magazines — more of a public arena than a gallery. There was a magazine called Psyclone, but I really didn’t like their content. I met Vale who was a rebel and I was yes. That was what I wanted to do. That was the trajectory.

S: You had no money but you did manage to get a Nikon FM camera.

RR: How did you know that?

S: I read your interview in Vice.

RR: [laughs] Actually I won that camera. I was using this camera my friends gave me and there was a photo contest in BAM Magazine — a rock and roll photo contest. I entered a photo and won the camera and was so freakin’ happy. That was a good camera. I still use Nikon. It was a picture of VS with the clouds behind them. It was cheaper to live back then. I bought an enlarger and was able to print in the bathroom. That’s when Vale and I moved to the apartment on Romolo. I printed in the closet. I had to make it light proof. But I feel like my mediums have been taken from me: film and slide photography. In the Eighties I did a lot of slide photography because I was doing projection shows with multiple slide projectors. But they stopped making slide film and they stopped making Ektagraphic slide projectors which was a beautiful system. Now you have to have a video camera and an expensive projector. Film slides were a cheap way of making projections and I really enjoyed doing that. I love film. I love the way it looks. I loved processing it. It’s silver. You can look at film in different types of light and see the positive and the negative at the same time.

S: You had Tri-X 400 film, the fastest film at the time which you needed to photograph punk bands and personalities in night clubs. In a lot of your shots it looks like you didn’t use a flash.

RR: Sometimes I did. Sometimes I didn’t. And then I used flash in tricky ways like with an open shutter to get the background.

S: How could you afford 400 ASA film which was expensive?

RR: How did I afford it? I didn’t eat hardly ever. I just had to make every shot count. I couldn’t waste film. A lot of my photos I just had to take. I would see a great shot and take it and it would be the last shot on my roll. Some of my photos you can actually see part of the top of the photo cut off because I was too far over on the film roll, but that was the last shot I had. I think my limitations helped me become a better photographer.

S: What camera do you have now?

RR: I’ve got a Nikon FM3 and I have a Russian Panoramic Camera — but I’m not crazy about that one. It has a moving lens to take a Panoramic photo.

S: Where did you find that?

RR: In New York City, the last time I was there about five years ago. I was using Fuji Panoramic Cameras and they stopped making those too! I’ve been so unlucky about losing my media. I was using panoramic cameras to make long mirrored images.

S: You took an iconic photo of Darby Crash that is on the cover of Don Bolles’ history of the Germs published by Feral House. The Germs were the first California punk band that really wanted to be big.

RR: I don’t know if they wanted to be big — but they really wanted to be influential. I don’t think they ever could have been big. They were too chaotic. They were an incredible band. Darby had such charisma and power about him when he was performing. He would jump down off stage and come up to you and you were scared. You didn’t think he was going to punch you, but he would confront you on a “soul” level. And that’s what I liked about him. That was a theme of punk: pushing your limits. Many people thought this was “violent” but… what he did to himself — that was violent, but he had gone into another space. If you look at this picture he is very hyper alert — he wasn’t “out of it.” He may have been, but he didn’t appear that way. He appeared to be in control.

S: Darby seemed to be emulating Iggy Pop. Posing shirtless, slashing his chest with glass and hyper alert as you said.

RR: Of course. We were definitely influenced by Iggy Pop. We loved Iggy Pop. The Stooges were an inspiration to so many people for sure.

S: This photo of Darby was shot at the Mab?

RR: It was taken the night after the Sex Pistols show at Winterland. This show featured the Bags, the Germs and some other band I don’t remember. So many people came up from LA to see the Sex Pistols and were still in town for this show. We knew that Sid Vicious and someone else from the Sex Pistols would show up at this Germs show. The Winterland had been the biggest punk rock event ever up to this time. About five thousand people or something. Of course everyone was really negative: hitting and punching. It was kind of scary for the bands that opened like the Avengers and the Nuns. I thought it was a great show myself. It was the epitome of everything that led up to it. This was our moment. So the next night was the show at the Mab with the Germs headlining. Sid came in when the Bags were playing. You could tell he was sort of out of it. He got on stage right when the Bags were still playing and slashed himself, just like Darby would do later in the evening. It was almost like Darby and Sid were having a battle between them. I don’t think they even talked that I could see. Sid ended up back stage after cutting himself during the Bags set. He was being very obnoxious. It was ridiculous and juvenile. Darby didn’t want to get upstaged and also ended up slashing himself.

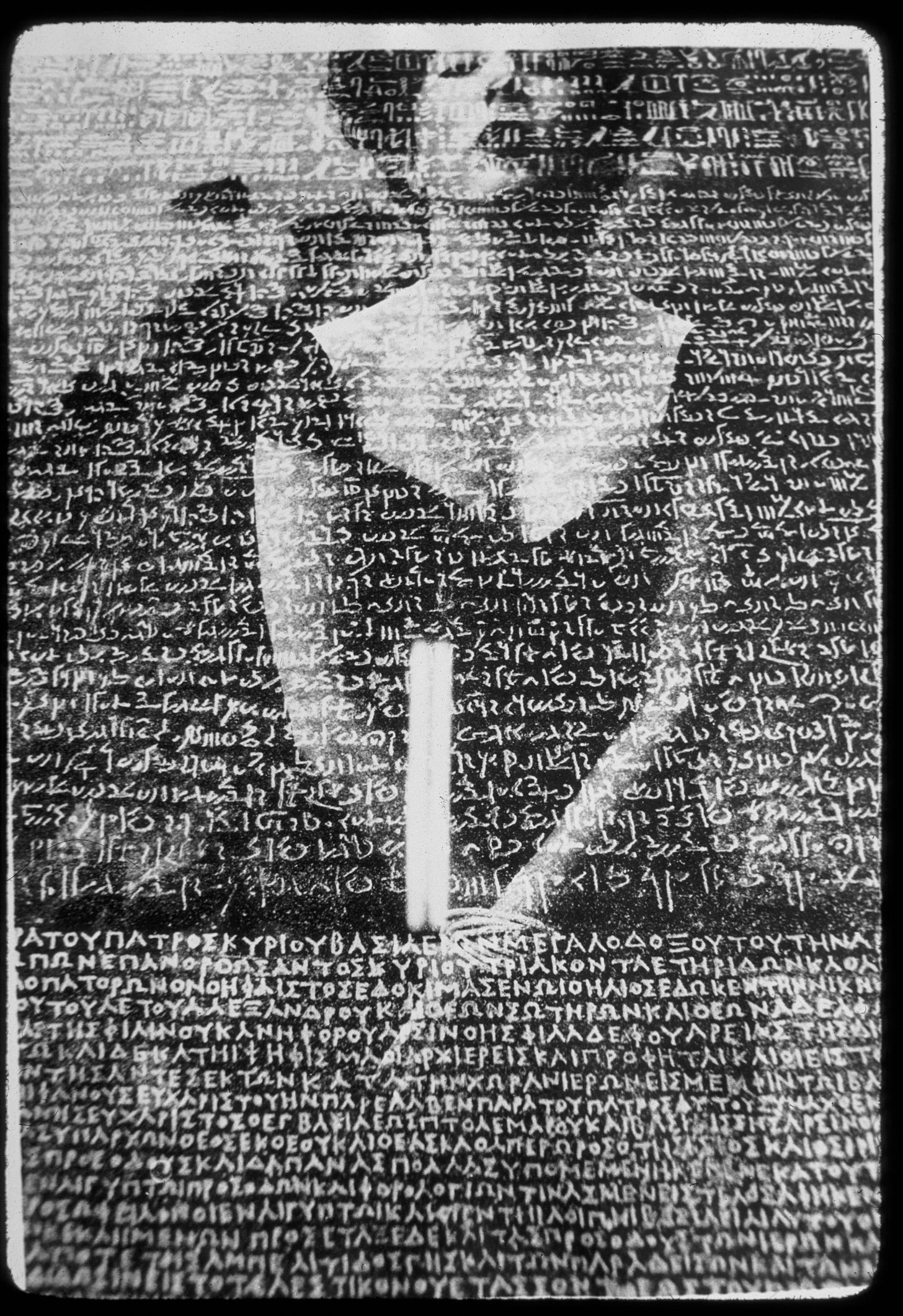

S: How did you get into Egyptology?

RR: I don’t remember. I was into Egyptian things before I went to Egypt. Maybe it was from working at Tower Records. I really liked Um Kalthoum. She’s worshipped around the world and I have a bunch of her records. I like that passionate sound and I love the rhythms. I was into Middle Eastern music at the same time I was into punk. I love rhythmic Egyptian folk music too. Umm Kulthum is more classical Egyptian music than folk. I guess my interest in Egyptology comes from my interest in the esoteric. I started reading work on Gurdjieff when I was living in Buffalo and that’s one of the reasons I came to San Francisco, because I knew they had a Gurdjieff group here. I couldn’t find that many books on Gurdjieff in Buffalo and there weren’t that many books on Gurdjieff then. More have been published since the Seventies. I did read Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous and Tertium Organum, the later being about how the Fourth Dimension is a reality. I read that in Buffalo at age 19. Books on Gurdjieff really opened my mind and I really tried to process this stuff. I’ve always been a studious person. I like to study. I like to study and I like to search out what I’m interested in. I was interested in the Gurdjieff work and he talked about esoteric art and conscious art. So, in a sense, I was interested in art even before I became an artist. Gurdjieff looked at the idea of a conscious art and asked where it could exist. He said it didn’t exist in modern times and that modern artists were wasting their efforts. He also talked about Egyptian music, dating back to antiquity, qualifying as conscious art. He specifically mentioned snake charming music. It was really the snake charming music that led me in. I really tried to find snake charming music that was alive in this time period and there really wasn’t that much. The Gnawa musicians play a modern version of it. There are also musicians in India that play snake charming music. I love the sound and the singing style. I really don’t know how to describe it.

S: So you went to Egypt?

RR: I did. I went to Egypt twice. My girlfriend Ivy and I were very close. She passed away. We went to London in ’78 and spent a month there. Then we got this urge to travel more and we went to Greece and spent a week there and then went to Egypt and spent two weeks there. We had an incredible time. It was just at the end of that period of time where they still had a liberal social culture. Now it’s pretty repressive with a lot of Islamic stuff. I went again in 1985 and spent 6 weeks there. If you look around my apartment, you’ll see a lot of Egyptian things. I’m kind of an Egyptian “fanatic” though I don’t own anything really valuable.

S: Can you tell me about your period with Saqqara Dogs in New York?

RR: Well I moved to New York with Bond [Bergland] and I still wanted to do art but no one, at that time, cared about my punk photography. I was kind of ejected from San Francisco — let’s put it that way — and New York wasn’t interested in San Francisco punk. It was a totally different scene out there. So I continued my studies and became more and more interested in ancient art and that became an influence on my own artwork. I was doing a lot of black and white photography, utilizing selective staining, so you have black and white prints that look like they’re color. I was living with Bond, who was in Factrix and Factrix made several attempts to remain active that didn’t pan out. Bond wanted to keep on playing music and we wanted to work together. I had done projection shows with Factrix — just small time shows — and so I wanted to keep on doing that, it tied in with a lot of things I was interested in: using colors and sounds and images and vibrations to alter consciousness. Once again this goes back to the Gurdjieff idea of making conscious art to wake people up somehow — rather than put them to sleep. Saqqara Dogs was a fantastic band and I loved working with them. I loved their music. There was a definite Middle Eastern sound to it because of the dumbek. Bond and I went to Egypt and that’s how we got the name “Saqqara Dogs.” We were in Saqqara and there were these wild dogs who would dig these holes in the sand and just lay there, so we came up with Saqqara Dogs. We did a lot of shows in New York, we did two small tours. We played the Walker Art Center and that was a good event. It all started to fall apart though, things happen. I would do the visual media at our live shows. I had four projectors and different polarizing screens that I would shine images through. I made little collages with tape and I would project the light through them with a polarizer and would move the collages around. I’d make overlays of the images and try to tell a story along with the music. I think we were getting pretty successful. I made a video of one of our songs that is on YouTube: “Greenwich Meantime.” That was a really intense song back then. The music was like a snake charmer’s song. Id be doing slides while they were playing it and I’d go into delirium projecting the slides. I think we were taking a lot of “X” back then too. The video is just slide after slide, because the software I used at the time was kind of primitive. The “Greenwhich Meantime” video has all of my Egypt photos and kind of tells a story. It gives you an idea of what I was doing in the Eighties. It’s a nine-minute song.

S: There are a lot of people who are skeptical of mystical anything and see Gurdjieff as one of many New Age charlatans. But I see him as a sort of psychologist.

RR: Well he was a psychologist and a mystic. A psychologist deals with the personality but Gurdjieff was trying to go beyond the psychological to the Eternal. I found his work very effective and I was involved in the groups for a while. But I don’t know if there are that many people that knew Gurdjieff when he was alive who are left. I think it’s all new people and I don’t know if it’s as effective.

You are still doing photography?

RR: Not in the same way. I haven’t done journalistic photography for quite a long while. I’m doing collage. I’ve been doing several things since I started back up with photography. When my son was born I sold my camera and I was kind of defeated when they got rid of projectors. I got into something else. I started to study healing. I was always interested in consciousness. As I sort of mentioned I worked in the Gurdjieff work for a long time. I got involved in other groups and studied healing for 10 or 15 years. I didn’t get back into photography until 2000 when a friend wanted me to look to look through some negatives to find some photos. I hadn’t looked at those negatives ever. I printed them after I shot them, then once again in 1983 to make a series of my best prints and then I didn’t look at them until 2000. So we were looking at the negatives and my friend said: “You’ve got a lot of really great photos here.” I looked at ‘em and thought that, yeah, some of them were really good. So I started scanning all of my negatives. I decided to start working on a book with my friend who I knew from Search and Destroy and it took us eight years to collect information and write about the early scene. At the last minute she dropped out of the project and that devastated me but I couldn’t stop working. I had to get the book out and I ended up making an e-book. So from about 2000 on I’ve been dealing with punk photography. Then my girlfriend Ivy died and that was also devastating. There was a lot of heartbreak between 2000 and 2010. But when I get upset I just work harder. I started taking photos of myself with the little camera on my computer. I’d take closeups of my hand or my eye and make collages out of those. I tried that for several years. I would make other kinds of collage. So I’m not going out and taking pictures really. I’m using what I have and making new things with it.

S: It sounds like a recombinant process.

RR: It definitely is. The photos I took with my computer camera are now suspect with the “Selfie Controversy.”

S: “Selife controversy?”

RR: Well everyone is saying people are taking too many selfies. The president takes a selfie in South Africa, people take them at funerals, the Kardashians are taking selfies a thousand times a day. But when I took these photos I wasn’t thinking about the “selfie” because that term wasn’t being used yet. I was just doing it as a process of self-examination. I was taking these photos and turning them into some kind of marvelous image that was shocking at the same time. I like to shock a little bit with my artwork. I don’t know if the punk stuff is shocking now. It was a little shocking then. I’ve had pictures published that are shocking. I like a weird beauty. That has always inspired me. You want to shock people into awareness. Like with Gurdjieff. If you’ve read Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous that’s the best description of some of the ideas, but the practice is pretty involved. It’s effective. It woke me up. Not permanently, but for a while. I’ve had a lot of psychic and other worldly experiences in my life and that’s probably why I was attracted to the Gurdjieff working. Just as a way to explain it to myself in a non-superficial way.

S: What else are you up to?

RR: I’m starting to get more jobs. People who want photos from the punk era are looking me up. I’m not making a lot of money. I am in the Mark Mothersbaugh Art Show that is traveling right now. It started in Denver. That’s Mark Mothersbaugh from Devo. The show is brilliant and funny. I met Mark at the Denver opening. I hadn’t seen him in 25 years and he was very friendly. There was a historic part of the show and I had some photos of Devo and he wanted to use them. So I ended up with my first museum show through him. I’m bringing what was hidden out. That includes other punk photographers as well, because there was a lot of great artwork that was never seen. Just like my own work. It’s so hard to get your art out. The Mark Mothersbaugh Show is sold out — so people are interested. A TV show is being made about Mark. I’ve had several solo shows since then. Two in Los Angeles and shows in Denver and Phoenix. I’ve been very busy promoting my work and that of others.

I just finished the Punk Renaissance and that took all year. When I started I didn’t know if I had the energy to do it, but I did it anyway. I did it to the best of my ability. I think we were very successful and I’m really happy about it but now I need time to get back into myself. Actually the thing I’m going to be working on is waking myself up. I’ve come close. I’ve woken up several times. I wouldn’t say I’m awake right now because we’re all living in a dream. There’s so much electro-magnetic stuff in the air. This city is getting so crowded and there are people walking down the street oblivious to everyone else. People don’t mind bumping into you and that used to be considered impolite. But now it’s regular behavior and people don’t apologize. I think people are more aggressive now. But we have to deal with whatever is going on. There’s no ideal world to work in. Maybe it’s easier if you’re living out in the woods somewhere and you have somebody guiding you removed from outside influence, but wherever you are is where you have to work. I’ve taken this to heart. I’m still going to do artwork because I’m very creative and I like to do things and make things. I just don’t want to be superfluous. There’s a glut of art and that presents problems. What is the value of art? Just to be collected? The good art is collected and the rest just goes away? Getting art to the people that they can utilize is more important to me. I like collaborating and I don’t want to just do the punk thing forever.

Great title and subheading. See, that wasn't so tough.